Monarch butterfly and dragonfly migrations are so massive they’re being caught on NWS radar

OKLAHOMA CITY - The National Weather Service’s weather surveillance radar captured a massive migration of monarch butterflies and dragonflies flying over the central United States.

The monarch butterflies and dragonflies were being carried by a north wind tailing behind a cold front that was passing through central Oklahoma on Oct. 5.

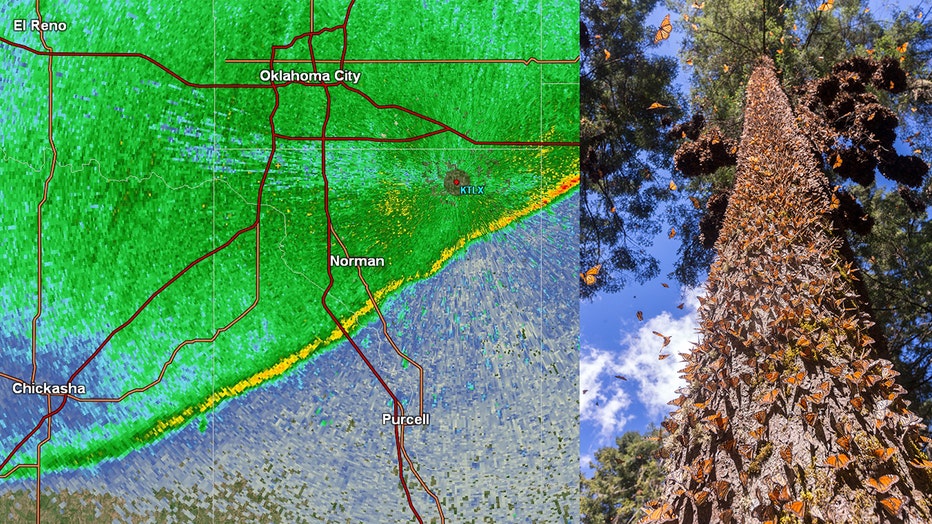

In the image shared by NWS, the colorful patches of the map reveal the extent of the migration, with the densest areas marked in yellow and red. This is the leading end of the migration, and the additional green areas mark the rest of the butterflies trailing behind.

Radars like WSR-88D, which captured the data, transmit 10 cm electromagnetic waves at the speed of light in the form of short bursts of radio waves.

These radio waves then travel through the atmosphere and will strike any present hydrometeors, such as rain, hail or snow, causing the radio wave energy to scatter in all directions. The energy which reflects back toward the radar is measured by a fine-tuned receiver, which can then determine whether the hydrometeors (rain/snow/hail) are moving toward or away from the radar. This is known as the “doppler shift.”

But weather phenomena aren’t the only thing that radar can pick up.

According to the NWS office in Boulder, Colorado, insects rarely produce a coherent radar signature, but migrating birds frequently do, and this has to do with size. Butterflies can show up on radar only in large enough and highly-concentrated quantities — like during a mass migration when the butterflies are flying with wind currents.

RELATED: Massive swarms of dragonflies in 3 states picked up on weather radar

Butterflies showing up on radar is such a rare occurrence, the NWS Boulder office originally guessed that a radar reading on Oct. 3 was showing a bird migration over Denver, but Twitter users quickly alerted the agency to the fact that it was a migration of painted lady butterflies.

Monarch butterflies are known for the extensive and massive annual winter migration that brings millions of them to California and Mexico. Their total migration path can be as long as 3,000 miles, and North American monarchs are one of the only butterflies to migrate such a distance.

They are driven each winter by a need to escape cold temperatures, which will kill them if they linger.

Monarch butterflies are migrating in such large numbers that NWS radar is capturing their path. LEFT: NWS radar image. RIGHT: Monarchs cover a pine tree in The Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. (Sylvain CORDIER/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images)

Monarch butterflies emerge from their chrysalises throughout the summer and into early fall, but their life cycles are different depending on when they emerge.

Monarchs born throughout the early and mid-summer have much shorter lifespans than those born in late summer and early fall, and only those that are born later will live to migrate south. Those that make the longest migration south are often referred to as the monarch super generation.

By the time the next winter rolls around, the butterflies heading south to migrate will be a few generations removed from the prior monarch super generation.

This story was reported from Los Angeles.