A year of Arizona's wet weather made a big dent in drought conditions – but how much?

A year of Arizona's wet weather made a big dent in drought conditions – but how much?

You might've guessed it. With a wet monsoon and a snowy, cold winter, Arizona's short-term drought from last summer has improved drastically. But are we out of the woods? FOX 10 Meteorologist Krystal Ortiz answers the questions you might have.

PHOENIX - During a snowpack survey on the Verde River Watershed this February, the Salt River Project (SRP) was thrilled at what it found.

"Woo, that’s deep!"

Four feet deep, to be exact.

SRP sends crews to monitor winter snowpack a few times each year – driving or flying – to spots like Happy Jack.

"Get on the snow shoes and go out to the designated areas and stick the federal sampler in the snow, take it out and weigh it, and we can get an idea of how much water equivalent to snowpack it is," said Bo Svoma, Salt River Project Meteorologist.

Or, how much water is in the snow, if it was all melted.

This season, you might've guessed, brought in huge numbers.

"Usually you come out here in late February and these sites will have like six inches of snow water equivalent," Svoma said. "Today we measured 13.3" of snow water equivalent, which is really impressive."

This year’s snowpack is the largest in three decades. As it melts, the water runs into small creeks and streams, like Clear Creek.

From there, it heads down stream to Horseshoe Reservoir, one of seven reservoirs in the SRP Salt and Verde system, which store much of the Valley's water supply.

The system is already at 100%. A big change from only a year ago.

Horseshoe was below 10% full in April 2022. It's now over 80% capacity.

As a whole, the Verde basin has seen over 400% of average snowpack. The Salt Basin has seen over 200% of average.

Bo Svoma, Salt River Project Meteorologist

Snow melt combined with recent rainfall forced SRP to release water for the first time since 2019. While the normally dry Salt River running with water is a sign of a healthy water supply this year, it doesn’t mean all our problems are solved.

"During a long term drought, we’ve pumped a lot of groundwater, as part of our conservative drought management plan. So the accumulating effects of three decades of pumping more groundwater than not, being in a drought is still there," Svoma said.

While the underground aquifers will get a break from pumping this year, they won’t be fully recharged.

"So we’d have to have maybe five more good years in the next decade to where we’d think, OK we’re out of the drought, groundwater aquifers are more balanced,'" Svoma said.

Arizona State Climatologist Erinanne Saffell says our water year, which runs from October to September, is off to a great start. But, there’s a big difference between short-term drought resolution,

and long-term drought conditions.

"Short term drought really is impacted by what’s happening with the precipitation. What we’re seeing right now, kind of like the ecosystem, the soil being moist, the plants are happy, and we’re really happy to see that," Saffell said.

Arizona State Climatologist Erinanne Saffell

The drought monitor tracks short-term drought immediate impacts based off recent weather.

With a wet monsoon and a snowy, cold winter, the short-term drought from last June compared to this April shows a drastic improvement. In fact, more than 80% of Arizona is no longer in a short-term drought at all.

No part of the state is in the highest tiers: extreme, or exceptional drought.

Remember, this only tells part of Arizona’s drought story.

"Really understanding where we stand in the long term, if we go back to 1994 or for the last 29 years, if we look at that, we’ve had 20 years that have been deficit, that have been drier than normal, and we’ve only had 9 that have been wetter than normal. So taking that into context is really important," Saffell said.

MORE: A look at Bartlett Dam as Arizona releases water after wet and snowy winter

A look at Bartlett Dam as Arizona releases water after wet and snowy winter

Because of our wet and snowy winter, Arizona has seen water releases from Valley dams that we haven't seen in years, including Bartlett Dam north of the Valley. So much water has been released there this year, it's equivalent to draining and filling Bartlett Lake three different times. FOX 10's Troy Hayden got special access to the dam to see how it all works.

Those hot and dry years have made our atmosphere "thirsty," Saffell says.

From soil and plants absorbing our runoff, to evaporation stealing from our reservoirs. It's a problem that becomes more obvious across the Colorado River Basin.

It’s a much larger basin compared to Phoenix’s Salt and Verde, and unlike in Phoenix, where water supply and demand are roughly equal, water along the Colorado River is over-allocated and often under-supplied.

Paul Miller is a hydrologist for the Colorado River Basin (CRB) where he tracks and forecasts water supply, providing valuable information to the Bureau of Reclamation which ultimately determines how water from the Colorado River is dispersed among the region.

"The hydrologic drought that my office deals with more deals with reservoir storage and long-term water supply, conditions for state use, large municipal use, and hydropower generation," Miller said. "Over at the Colorado River Basin, what we’ve seen this year has been really great. It's a stark contrast to last year when we saw 50% of average and below."

Paul Miller, hydrologist for the Colorado River Basin

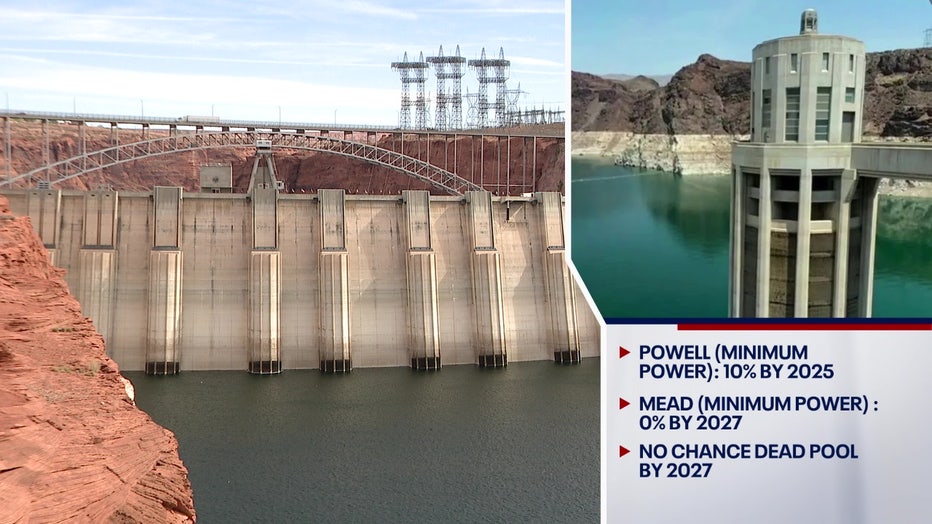

Snowpack over eastern Utah and Colorado are also running above average this year, which will help Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

Latest projections have runoff into Lake Powell at up to 175% of average.

"Lake Powell is expected to rise a pretty decent amount, but still overall conditions are low in the reservoir. The drought has been going on in excess of 20 years, so one good isn’t really enough to get us out of that," Miller explained.

Miller says the latest forecast has Powell rising around 35 feet from a current 23% capacity to at least 32% full. Improvement, but not enough.

Long-term drought is still embedded.

"Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the combined storage between those two reservoirs is really a good indicator of the overall hydrologic health and the water supply of the Colorado River Basin and despite this really good year, the storage capacity, the combined storage capacity of those two, is going to be well below 50%," Miller said.

According to Miller, Mead and Powell had a combined storage of over 90% around the year 2000, which has allowed Arizona to still have water, even after two decades of drying in the region.

Can we ever get back to a healthy water supply in the Colorado River Basin?

"We would probably need on the order of 6 or more consecutive years of this kind of snowpack to really get back up into those ranges where people started to feel more comfortable with the water supply," Miller said.

While that is unlikely to happen, there is some good news.

The Bureau of Reclamation’s latest models indicate it’s very unlikely Powell or Mead will drop below minimum to create energy in the next several years. Even better, their projection now gives no chance of Mead or Powell dropping to dead pool through 2027, meaning the reservoir is expected to have enough water to flow downstream.

"It’s a small step toward where we need to go, but at least it’s a step forward in the right direction. This is definitely a win for the Colorado River Basin and yeah, the more years we can get like this the better," Miller said.

Continuing coverage:

Floodwaters from recent winter storm prompt evacuations in various parts of Arizona

Another winter storm has brought a lot of rain to various parts of Arizona, and on Mar. 22, floodwaters have resulted in evacuation orders being issued for a number of communities across the state. FOX 10's Lindsey Ragas, Linda Williams, and Nicole Garcia report.

Salt River bed sees lots of water as SRP conducts dam releases

A rare sight in the Salt River bed in west Phoenix over the weekend —water! After several days of SRP releases from dams northeast of Phoenix, the water made its way to the west Valley. FOX 10's Linda Williams has more.