Survivors share stories of their time in Japanese internment camp in Poston, AZ

POSTON, Ariz. - It's been nearly 80 years but the history of Japanese internment camps still haunts the victims.

"The fear on my mother's face, that's ingrained in my memory," said Norman Ikeda, incarcerated at age three.

Dozens of Japanese Americans make the "Poston Pilgrimage." First, second and third generations gather at the monument looking back on how one day changed the world.

As America entered World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued executive order 9066 with the goal of stopping espionage and to protect those of Japanese descent from violence.

Nearly 120,000 Japanese people living in the U.S., 70,000 of them American citizens, were sent to ten internment camps. About 18,000 were imprisoned at the Poston relocation center just 12 miles south of Parker, AZ.

With just days to pack their items, families boarded trains and buses for the unknown. At 6-years-old, Ruth Okimoto and her family left San Diego, taken away by soldiers armed with rifles and bayonets.

"The government put us on a train and sent us to the Colorado Indian reservation and there we stayed for the next three years," said Ruth Okimoto, incarcerated at age six.

James Tajiri, also from San Diego, spent his teenage years incarcerated sleeping in a barrack.

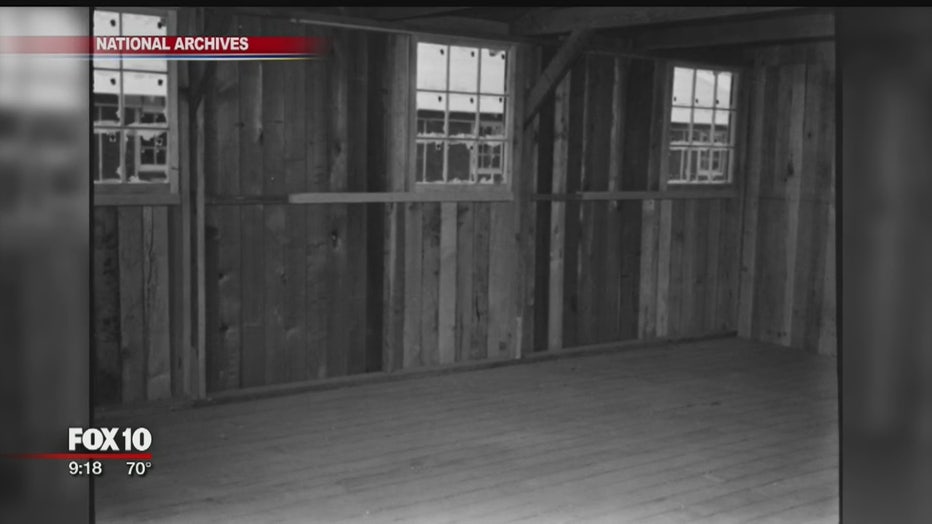

"It was a small room 20 by 25-square-foot room and when we went in the first day we had nothing there but a cooler and a heater and one light bulb," said James Tajiri, incarcerated at age 15. "We had a pillowcase but we filled it with straw."

Tajiri tried twice to enlist in the army but was rejected for being Japanese.

"I bought a Greyhound bus ticket and went back to Poston," said Tajiri.

Tajiri finally got drafted, but the war ended before he completed basic training. He still went on to do tours in Korea, Japan and Vietnam, spending 20 years in the army.

For children, Poston meant exploring the desert.

"Under the barracks there were scorpions and we would catch them, I mean lasso them, tie them together and let them run around," said Ikeda.

The inmates of Poston made the best out of the situation, even building their own school and irrigation system. Norman Ikeda says his parents never showed frustration of being incarcerated.

"Our parents are known as the quiet Americans, they didn't complain about anything," said Ikeda.

Now, 77 years later, survivors are speaking out, telling their stories and reflecting on the injustice they lived through.

"It was a concentration camp," said Okimoto. "The only difference between America's concentration camp and what happened in Germany and Italy and everywhere in Europe is that they didn't send us into the gas chambers."

Ikeda believes there are parallels between the Japanese internment camps and the crisis at the U.S. - Mexico border.

"What's happening at the border is exactly the same thing that happened to us but it's worse because they're taking the kids away from the parents," said Ikeda.

For some survivors, Poston is their second home.

"Poston is a part of you, it's embedded in my blood," said Okimoto.

Making the pilgrimage means something to survivors, a past you don't run away from but fully embrace.

"Poston means a difficult time in American history that I hope doesn't repeat itself," said Ikeda. "That's what Poston is to me."

In 1998, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, legislation with a formal apology, that paid $20,000 to each surviving victim who made it out of those camps.